The Big Short prototype: The Fed will reverse the deflation!

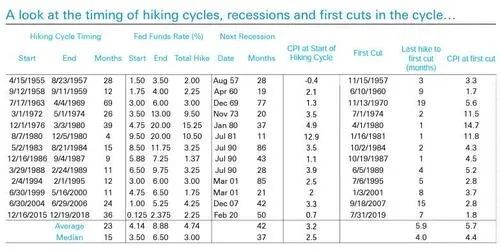

When consumers are reveling in the “unprecedented” seasonal promotions, little do they know that U.S. retailers are facing the worst “inventory crisis” since the Internet bubble burst.

On Monday, Michael Burry, the protagonist of the movie “The Big Short”, who was famous for predicting the 2008 economic crisis, said that the “Bullwhip Effect” in the retail sector would lead to a reversal of the Fed’s interest rate hike.

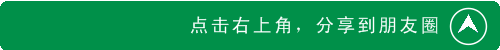

So, what is the Bullwhip Effect? It refers to the amplification and variation of the demand in the supply chain.

In the supply chain, small changes in demand will be magnified step by step from retailers to manufacturers and suppliers, and information sharing cannot be effectively achieved among them. This distortion and amplification of the information seem like a bullwhip graphically, so it is named the “Bullwhip Effect”.

A year ago, the global supply chain was in turmoil. At that time, problems of supply gaps caused by the pandemic were serious. Retailers and wholesalers rushed to purchase goods to replenish their inventories for the fear that they would run out of stock, which also led to the “resonate” in the primary manufacturers, thus raising prices and expanding the production simultaneously.

However, as demand gradually cooled, retailers’ inventories surged, and they even rushed to clear excess inventories, which led to a rapid plunge in prices of many core products.

As things progressed, the impact gradually penetrated the core inflation level.

According to Michael Burry, the previous oversupply in the retail sector leads to the “Bullwhip Effect”. However, with the slowdown in demand, the “Bullwhip Effect” ends and will trigger deflation later this year. This prompts the Fed to reverse the tightening path or even restart the quantitative easing policy.

Is the “After a tight first stimulus” trap hard to escape?

The “After a tight first stimulus” is a typical trap in policy that perplexed many western central banks in the 1970s and 1980s. It still haunts some developing countries even to this day.

In short, this trap can be described as the currency policies of the Central Bank changing between low inflation and high growth repeatedly, eventually failing to balance these two goals.

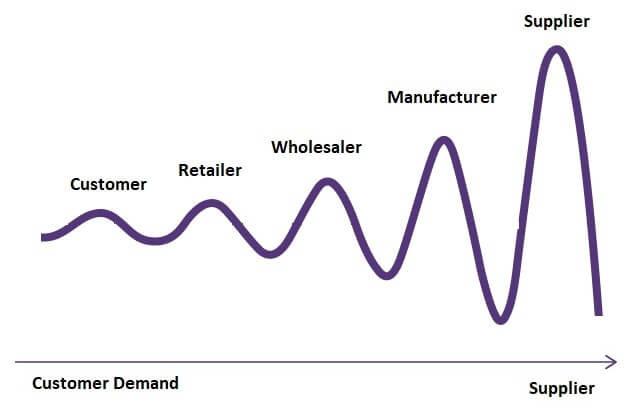

It is notable that historically, the event that the Federal Reserve cut interest rates immediately after a rate hike hadn’t happened, and it may even occur more often than you might think.

The above chart shows the U.S. median CPI at the start of each of the Fed’s 13 rate hike cycles over the past 70 years, as well as the value of the CPI at the beginning of the interest rate cut cycle after the interest rate hike cycle.

The chart shows that there is often just a four-month gap between the last Fed rate hike and the first rate cut.

In addition, the median CPI was still reaching up to 4.4% at the time of the first interest rate cut, which suggests that the Fed’s decisions on the interest rate are mostly based on looking ahead rather than on what is happening now.

Moreover, there are many periods in history when the Fed restarts the interest rate cuts even though inflation remains high.

Although history does not simply repeat itself, it always has similarities. Many analysts also said that it was highly likely that the Fed would fall back into its historic pattern of “raising rates before reducing them”.

There may be a “stop” in the rate hike this year

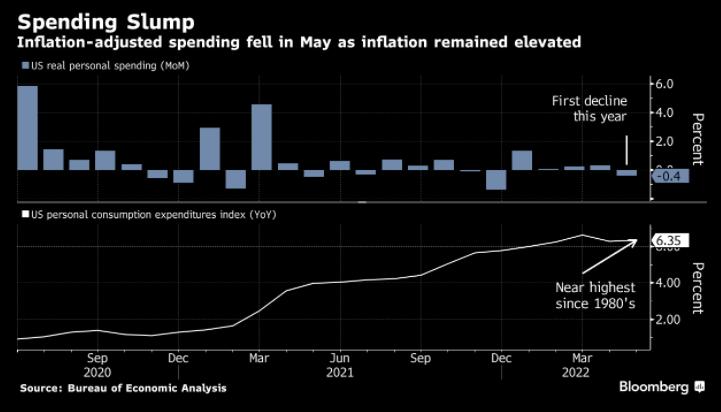

On Thursday, the Commerce Department announced that the core PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditure) Price Index growth had reduced to 4.7% in May.

The above picture is the Fed’s preferred inflation indicator. The slowdown in the PCE price index means that inflation besides food and energy is no longer “high,” and there is evidence that inflation is peaking.

With the 10-year yield falling from 2.973% to 2.889%, it doesn't seem easy to return to 3% again.

Except for the emergence of an inflationary inflection point, the more important reason for the plunge in Treasury yields is the growing evidence showing that the economy is in recession.

Markets have already coped with the possibility of a rapid Fed policy reversal.

Investment strategists in Mauldin Economics think that the Fed might call a halt at its meeting in late September; however, “stop” could mean a quarter-point rate hike rather than a 50 or 75 basis point increase.

Suppose the Fed has considered that the core inflation has mitigated and is truly aware that the economy is slipping into recession. In that case, they could resume quantitative easing policies even if inflation fails to reach its ideal target of a 2 percent yield.

In other words, perhaps we can see the Fed slowing the pace of tightening before the end of the year, while a policy reversal to start cutting rates is not so far away.